Jay and I went to Valley Forge on Friday. I’ve mentioned before that I’m a history buff, and I love refreshing my old lady brain about our amazing American history. Of course, the sad part is that everything connected with the Federal government is closed, but in this case, that just meant the Visitor’s Center. Outside the building were maps of the grounds, and an online recording was available from the website.

Here we saw some beautiful Fall color changes:

These were right around the Visitor’s Center:

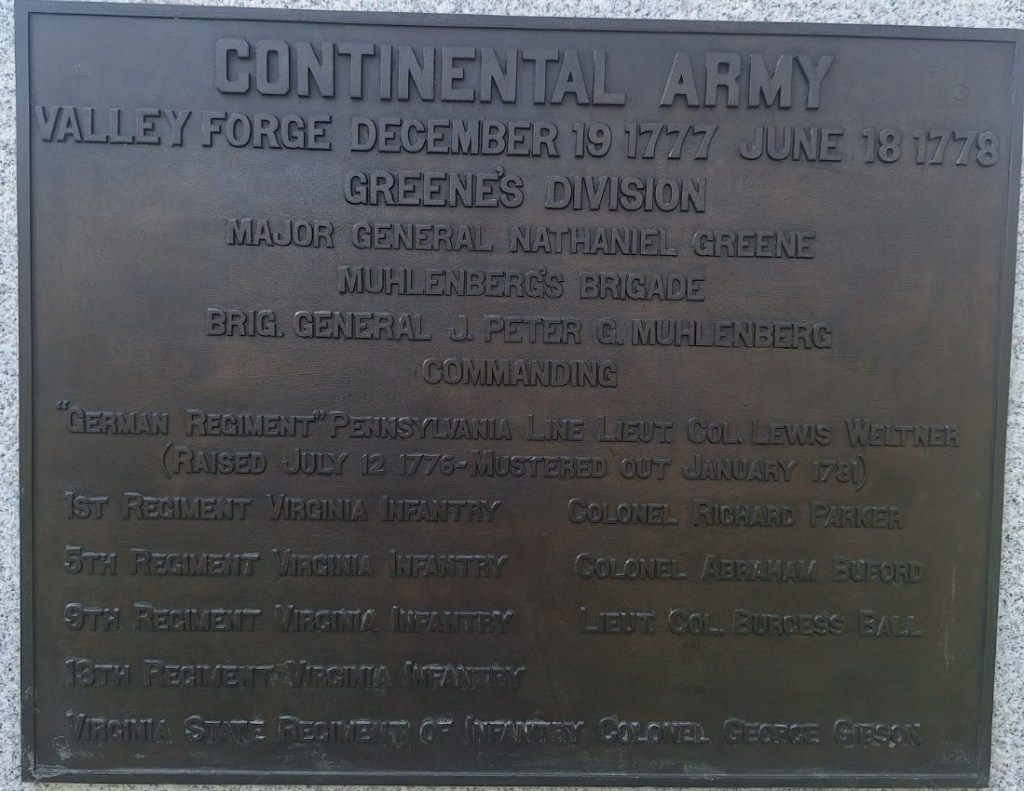

As you likely know, there were groups of military armies from each of the thirteen states. This plaque was for the Continental Army:

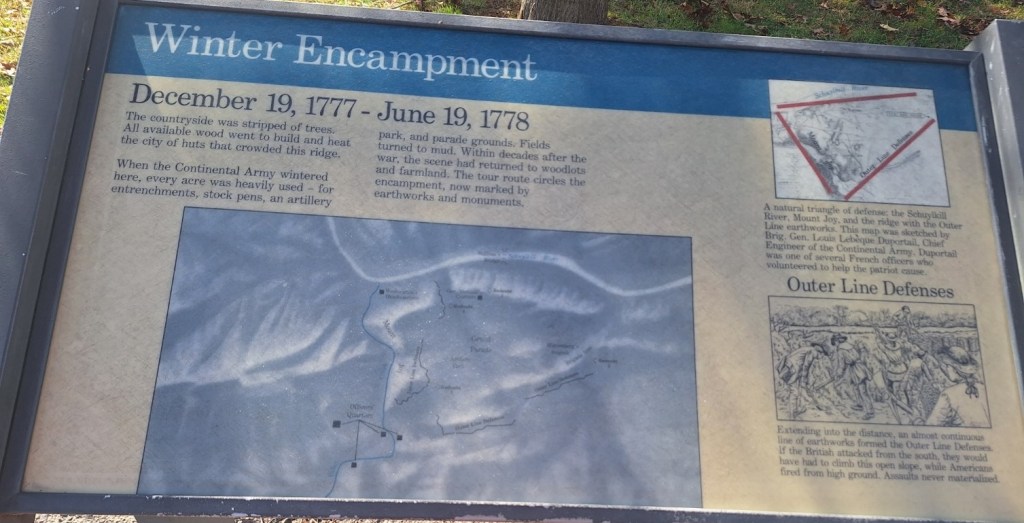

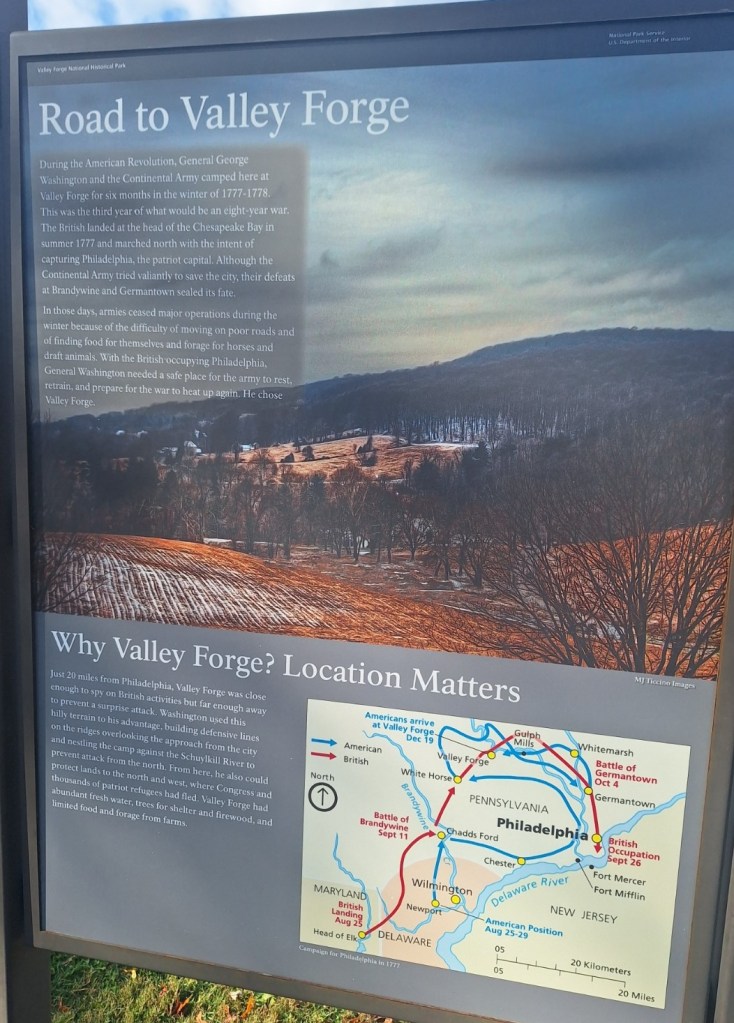

From December 19, 1777, through June 19, 1778, the men, along with George Washington, who stayed with his men, camped here. It was cold, and food was soon lacking:

This was a front-line position and necessary to have any advantage over the British Army. Location matters. It was close enough to spy on the British, but far enough away to prevent sneak attacks. It’s also filled with ridges and hills that provided good defense lines. A river ran behind them to prevent attacks from that direction. Finally, it overlooked the city of Philadelphia.

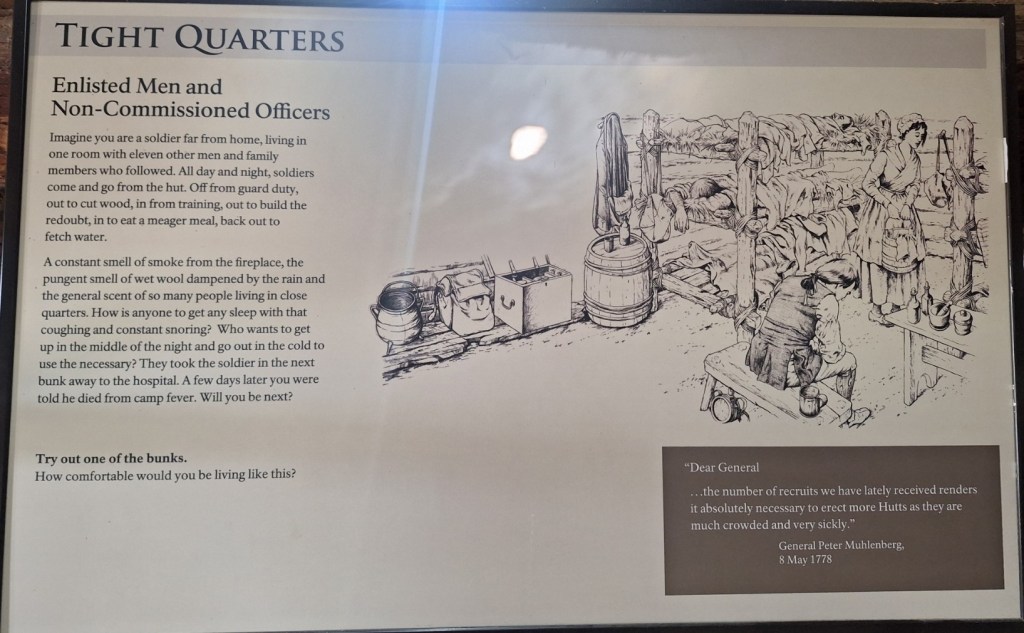

The first thing you drive to are the cabins built by the soldiers according to General Washington’s instructions. These small cabins slept twelve soldiers! There were so many, it was as if a city of huts had grown up within days. They built three high bunk beds, and there was not a lot of room between them. I’m pretty certain my claustrophobia would be kicking in!:

At the center back wall was a fireplace to keep them warm. All cooking appears to have been done outdoors.

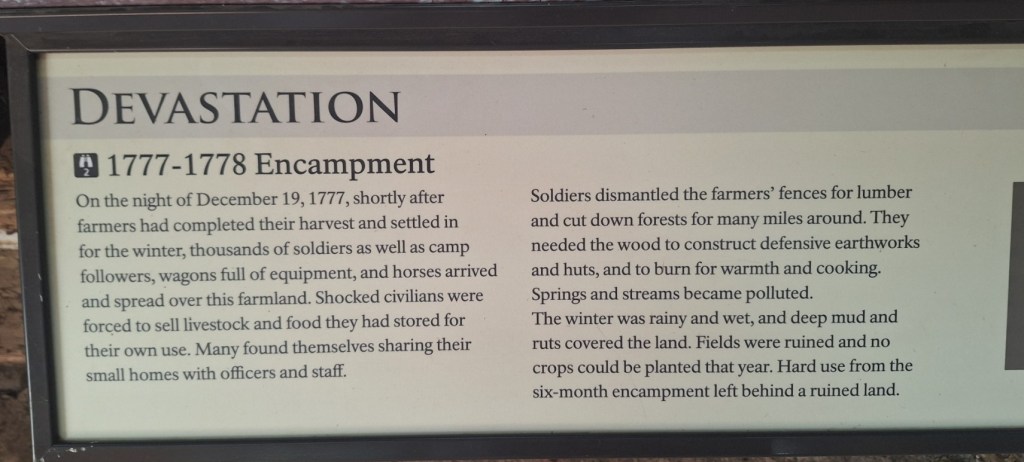

Of course, people lived in this area. Farmers, both well-to-do and poor, dotted the area. They had just finished their harvests and stocking up for their families for the winter when thousands of soldiers, camp followers, wagons filled with equipment, and horses came upon them. The farmers were forced to sell their livestock and the food they’d stored for their own families. Some had to share small homes with officers and staff. The army took down fences to use the lumber and cut down many trees, devastating the forest in the area to build huts, create defensive berms, and to heat the huts. It was a muddy, wet winter. The land was completely ruined by the six-month stay. The damage to fields was so bad, no crops could be grown the following year. However, within a decade, the forest had grown back strong. Still, that’s a lot to ask of people. I’m sure plenty were not very happy about it.

Enlisted men and non-commissioned officers were a ragtag group of people from many countries speaking many languages. Some had their wives and children following them into war. And many distrusted their fellow enlisted as much as they distrusted the British. It’s a wonder we actually won the Revolutionary War. But George Washington had a knack for bringing people together, and that’s exactly what he did.

Some sections in the huts were behind glass to protect the items on display. These photos will not be great due to glare, but you’ll still get the idea of what was there. For example, these shelves where items were stored. Not being as wide as the bunk beds is what distinguishes them as storage:

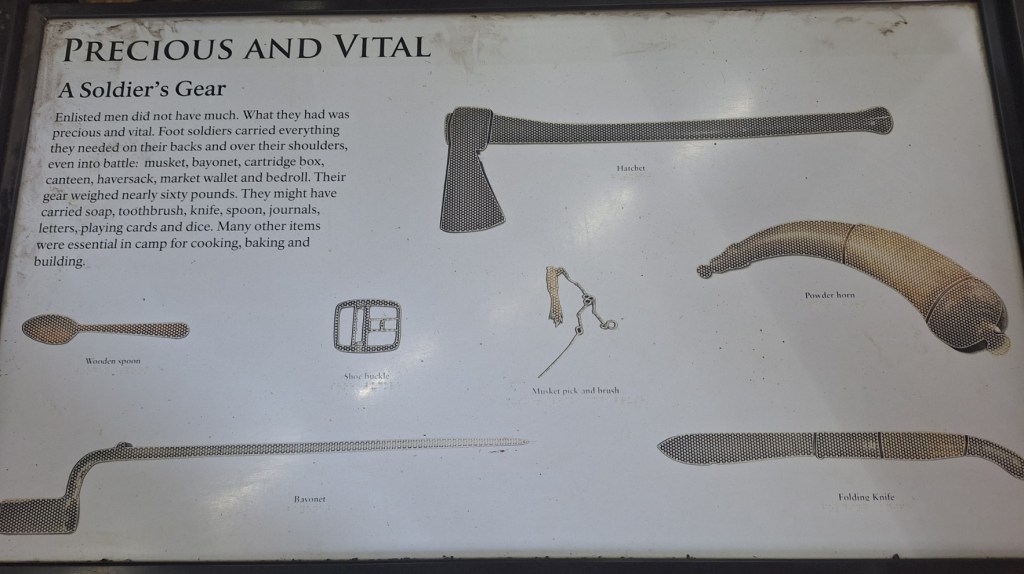

Each soldier was given a specific set of items for their jobs – I’m hearing Liam Neeson’s line in Taken, “…what I do have are a very particular set of skills, skills I have acquired over a very long career. Skills that make me a nightmare for people like you.” I’m not sure these items made the soldiers’ nightmares for others, but these were the items each received:

Their gear, much like our soldiers today, weighed around sixty pounds. I think our current soldiers carry more, actually. A bedroll, musket (rifle), cartridge box, canteen, haversack (the sack they carried everything in), a market wallet (a bag for purchases, like food), and maybe soap, toothbrush, dice, journals and letters, and playing cards, along with the items in the photo above. They were vital to their survival.

The whole thing sounds horrible. So how did they entice men to sign up? If you can believe it, this was the offer:

Clothing on their backs and food in their stomachs. Or land and a paycheck (which didn’t always come toward the end of the war).

Times could be that desperate for some. Others joined in a quest for the liberty and freedom they desired. Some for the adventure. And some to uphold the Declaration of Independence and defend the new United States.

These might be some of the types of food on the table:

An officer’s hut might look like this:

And a drawing for a better idea of what the huts may have looked like with all those soldiers crammed inside:

An outdoor oven built into a hill:

And a fire ring:

This is the National Memorial Arch at Valley Forge. I love how the flag stands in the center:

The top says:

Naked and starving as they are, we cannot enough admire the incomparable patience and fidelity of the soldiery – Washington at Valley Forge, February 16, 1778.

Columns along the roadway. Those are eagles on top:

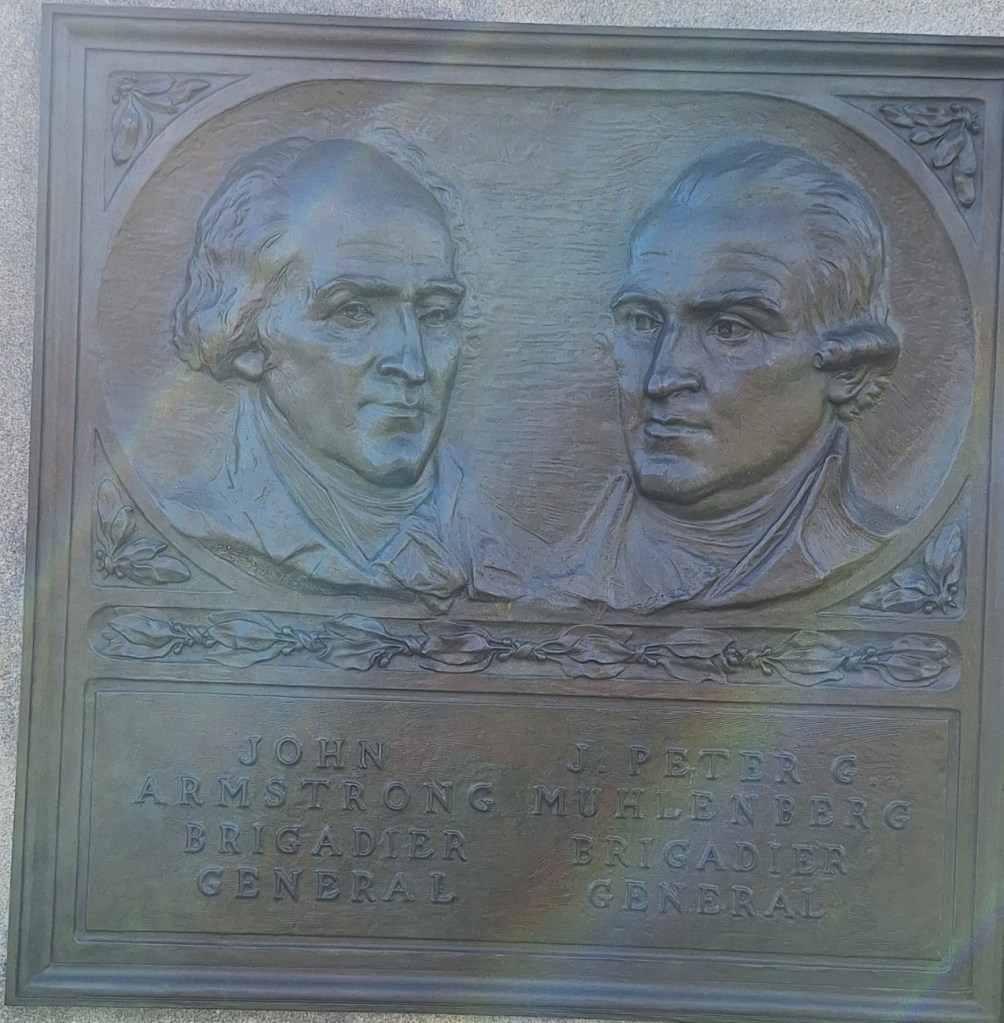

The plaque at the bottom of the right one with John Armstrong and J. Peter G. Muhlenburg, Brigadier Generals:

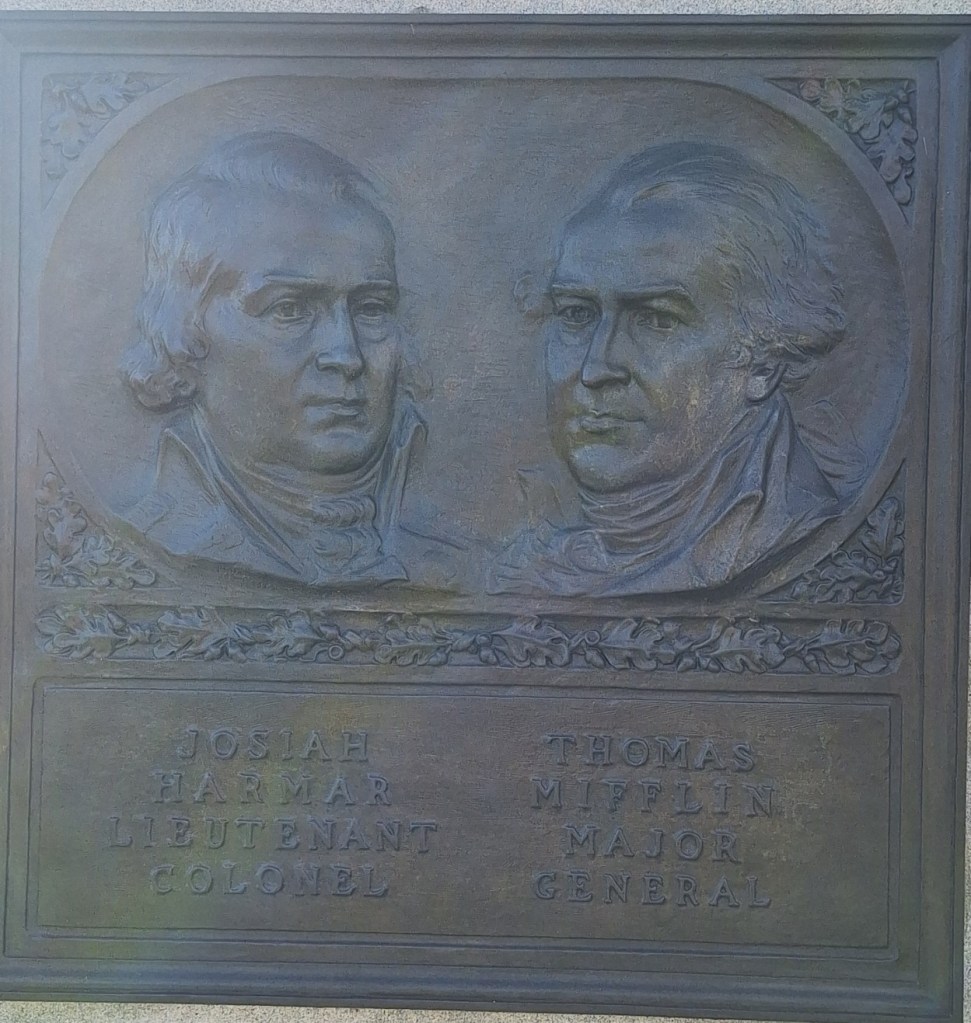

And the left plaque, Josiah Harmar, Lieutenant General, and Thomas Mifflin, Major General:

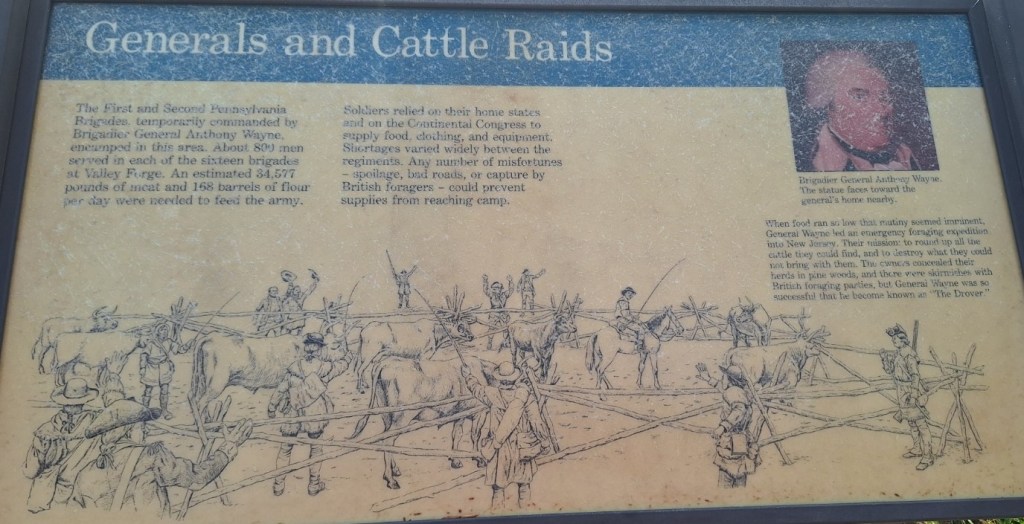

This next sign was pretty damaged. My guess was that the sun caused it. It was about the generals and cattle raids. Good heavens!:

This was the doing of the temporary Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, also called Mad Anthony, due to his aggressive tactics, who commanded the first and second regiments. Here is a statue of him on his horse:

I couldn’t get a photo of the front due to traffic and the sun, so you get a free stock photo. Sorry about that.

And last but not least, the house used as Washington’s headquarters at Valley Forge. It is also known as the Isaac Potts house. It has had two additions added to it since the 1700s:

My phone/camera ran out of juice at this point, so I have to try to remember the breakdown. From the left to just past the door was the original 1777 house. Then the area from the door to the end of the white part was added in the early 1800s. Later, the dark stone sections were added. That’s according to a sign on the site, but I can’t find that breakdown online.

Next Up: Day 83 – A Short Ride

Love the fall colors!

Do you get the feeling of reverence when you go to historical sites like this?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely. In fact, at our next stop in Philly, I got choked up. I’ll blog about that later, probably tomorrow.

LikeLike